|

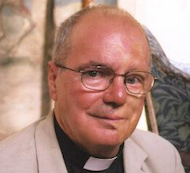

The Rev Dr Peter Mullen attended WLHS in the 1950s. He is a priest

of the Church of England and former Rector of St Michael, Cornhill

and St Sepulchre-without-Newgate in the City of London. Mullen is

Chaplain to the Honourable Company of Air Pilots, one of the Livery

Companies of the City of London and the Anglican Chaplain to the

London Stock Exchange, a largely honorific and historical post.

He has written for many publications including

the Wall Street Journal.

Further biographical

details on Peter Mullen

|

|

|

I was talking with some children at a christening

party: "I expect you're looking forward to the school holidays?"

Long faces. "No, not really." What, children dreading

the hols? I said. "Why not?" And they answered in chorus:

"There's nowt to do."

Despite being better off than previous generations, with more advanced

toys and games and technical gizmos, today's kids are in some important

ways the most deprived.

They have very little independence and even less freedom.

Hysterical fear of child-molesters means many children are driven

to school by their parents and driven home again at teatime.

And when they are off school, they don't play out as we used to

do. Instead, they spend hours in their bedrooms staring into the

computer or watching reams of ghastly stuff on television.

Those children at the christening party asked me what it was like

when I was their age. "Oh," I said, "you mean in

the olden days". I told them about growing up in the back streets

of Leeds in the Fifties and of how we didn't have television and

there were no computers or mobile phones.

They stared at me as if I had been some pitiable, impoverished wretch.

With no computer, telly or mobile, how ever did I fill the time?

Wasn't it boring? I told them that boredom was the very last thing

to occur to us.

My mother used to give me four pence each day for my bus fair, but

I used to walk or trot to school and spend the money at Mrs Pearson's

tuck shop. [ me too in the 60's -JS]

There, you could buy a pennyworth of hot fresh bread and a halfpennyworth

of butter.

Or for tuppence you could have a jam and cream long bun. As we got

a bit older, things got even better. Mrs Pearson's shop had an upper

room where, at lunchtime, she would let us go and listen to the

Test Match on the wireless - and, I'm afraid, smoke.

There was never any question of staying in your bedroom, except

for sleeping. The whole point of childhood, as I recall it, was

to escape your parents and play out. Doing a few jobs and running

errands were an occupational hazard, an irritating interruption,

a necessary evil, and you got them over and done with as quickly

as possible.

But the worst any of us was asked to do was queue at the Co-op for

a cabbage or half a pound of lard. Playing out meant nothing in

particular, nothing elaborate anyhow.

Chucking a ball against the wall - until the neighbours came out

and told you off for making a noise. Hopscotch. Hide-and-seek in

the side streets and alleys. Cowboys and Indians over the roofs

of the outside loos.

But the summer holidays! Nowt to do? We would have scoffed at the

very idea. Every morning I went off with Michael Hanson, Roger Hodgson

and Rod Boom to a bit of spare land which was misleadingly referred

to as "the gardens". Here we played makeshift cricket

all day. Or we would go into Armley park and roller-skate around

the bandstand.

We were warned strictly never to go near the canal. So, of course,

we did. There was a pipe that stretched across the canal and we

used to run across it - only very occasionally falling in among

the discarded bikes and old prams.

Dread the holidays? You must be mad!

Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive, and to be young was very

heaven!

|