| A

Tale of Two Schools.

Extract from"A personal reflection

on two schools" by John Wardle

For the unabridged version

see http://cgsfpa.co.uk/Articles/Cannock

Grammar School_JWardle.htm

Foreword In

1959 John was parachuted straight into the 6th form at West Leeds BHS. His previous

school couldn't have been more different. Cannock Grammar School was a modern

co-educational school, opened in 1955, so the transfer to Edwardian, single sex,

West Leeds , was a culture shock to say the least. He must have had a good testimonial,

however, because he was immediately appointed a prefect.

|

| First Impressions. I

had been over the Llanberris pass once, so such scenery as the Pennines was not

entirely unfamiliar, but Holm Moss was like driving up Snowdon. Mr Morton's vintage

car did manage two thirds of the climb before the tell-tale signs of impending

doom manifest themselves to its passengers. The car gradually slowed to a stop

as the passenger compartment filled with smoke. It was not just a stroke of luck

that an AA man turned up on his combination motorcycle just at that moment. He

had been watching the little car, streaming smoke like the tail of a comet, from

his permanent station at the top of that mountain. "'Appens all t'ime lad",

he told the esteemed teacher and proceeded to fix a burst oil pipe which had burst

like a blood vessel under the strain. Yorkshire folk were no respecter of persons,

whatever their status, as I was to find out.

In those days, the descent into

Leeds from the Huddersfield Road gave a unique panoramic view of the vast city,

with the outstanding landmarks of the Town Hall and University towers penetrating

the smoky haze. The outlook on that bleak late afternoon in December 1959 reflected

my gloomy feelings. They were not enhanced by the blackened millstone grit buildings

set in cobbled streets, which included Leeds prison which I had to pass on my

way to my new home. "And they called the Midlands the Black Country?" These

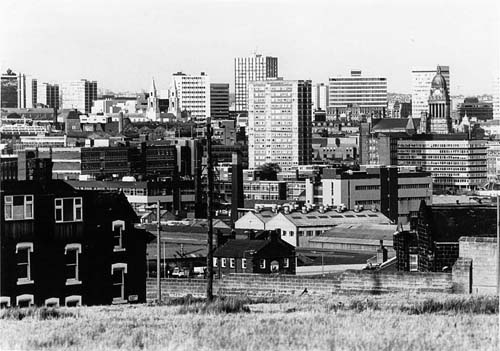

photos give you some idea of John's first sight of Leeds and Armley. |  |  | A

view of Leeds landscape in the 1960s. The A62, Gelderd Road, from Huddersfield

runs past the Jewish cemetry (Centre) . St Bartholemews Church Armley is visible.

| Leeds city center skyline taken from Armley,1963.

Armley jail is partly visible on the right.The Town Hall is top right. | Stranger

in a strange land There was a lot for me to get

used to, not least the culture, language and attitudes of this bleak moorland

county. It is well summed up in their great Yorkshire maxim:

Hear all, see

all say nowt.

Tak' all, keep all, gie nowt

Hear all, see all say nowt.

Ate

all, sup all, Pay nowt,

And if tha iva does owt fo nowt, do it fo thysen.

It

would not be unfair to describe Yorkshire 'folk' as proud, dour, selfish, abrupt

and opinionated but for all that, direct, honest, considerate and companionable.

They idolised their heroes and still do: Alan Bennett and Barbara Taylor Bradford

who lived down the road from me, J B Priestly and the cricketers Freddie Truman,

Geoffrey Boycott and Brian Close. The County was mortified when Yorkshire got

beaten.

It was a lot to get used to, not least the common language, dialect

and simple words like 'owt' - anything; 'appen' - perhaps; 'clout' - clothing;

'na'then' - hello; 'o'reight' - how are you; 'side' - put away; 'brass' - money;

'thysen' - yourself, 'frame thysen' - get yourself organised; 'ginnell' - a narrow

alley and 'tha'll niver stop a pig in a ginnel'l - you're bow legged. To earn

a bit of 'brass', I became a weekend milkman and found that an excellent way to

learn the geography of West Leeds, its culture and language.

I soon discovered

that Leeds was an outstanding city of culture and opportunity. The local Methodist

church that I joined had a congregation of 300 and a choir of 80 regularly performing

oratorios. International events such as the Leeds Piano festival were performed

in the iconic Leeds Town Hall; theatres including the famous City Varieties, cinemas,

dance halls, and clubs, especially the Leeds Mecca, were packed; brass bands played

everywhere and bus and tram services ran every thirty seconds. There were annual

events such as the Great Yorkshire Show, the Easter steam train exodus to scale

the Three Peaks and the grand Christmas 200 strong choir performance of Messiah

at Oxford Place Methodist Chapel to a congregation of 1,500. All this took place

in the foggy, blackened city in the heartland of Yorkshire's 'woollen district'.

It was a mesmerising contrast to anything I had previously experienced in the

rural outpost of Rawnsley's tin mission hut on the edge of Cannock Chase.

|

Settling in- The Lower Sixth

In January [1960] I attended West Leeds Boys High School. It was an imposing four

storey Edwardian Baroque building built in 1907. It had two grand first floor

entrances with stone steps, one to the Girls' School and one to the Boys'. It

was reminiscent of the invisible divide at Littleworth Secondary Modern School.

The boys now occupied the whole school as the girls had relocated to newly built

premises in September 1959 four months before I arrived. For me' going back to

a single sex school was a retrograde step and I was very conscious of it. The

sense of chauvinistic segregation still pervaded the place. As I mounted the steps

of one of the grand entrances I felt like a Cardinal Archbishop being sucked into

the Vatican, losing the freedom of his diocese and ending his days in an enclosed

order.

Mr Pomfret Headmaster of Cannock GS] had introduced me to the school

very well; a bit too well as it turned out. I no sooner stepped over the threshold

than I was made prefect. Here the prefects had manifest privileges. They were

the only pupils permitted to use the front entrances and the upper and lower sixth-form

prefects had separately assigned common rooms with sofas and settees. In the fifty

years of its existence the school had acquired status and expectation. It expected

to win the regional schools rugby championship every year; it had cabinets full

of sports trophies from swimming to cricket and expected to achieve at least two

places to Oxbridge every year. A well-established Old Boys' Society was centred

around the West Leeds Old Boys' Rugby Club which they had built for themselves

and sponsored. The ethos of that society exerted considerable influence over the

school and members held seats on the Board of Governors.

I

was made to feel very welcome by members of the sixth as much as a curio as anything

else. They wanted to know my nickname at Cannock; everyone had nicknames. I lied:

I said the school was too new to have the tradition of nicknames; it was the only

aspect of Cannock Grammar School I was happy to drop, so I was given a new one.

This

new academic spectacle was for me bewildering, faintly amusing, self-serving and

exemplified by the school motto, "Non Sibi Sed Ludo"; not for self but

for school. The regular Army and Airforce uniformed cadet parades that took place

in the school yard were amusing. They were commanded by Tisch Bein, the handlebar-moustachioed

German teacher, and taken very seriously. There were, however, benefits from joining

the military; the sixth-form air-force cadets did get to fly in aeroplanes and

it was expected that some of the cadets would become commissioned officers.

I

was tested from the outset. Unfortunately, Mr Pomfret had let it be known that

I was a good swimmer. Needless to say, for four lengths of Armley baths, I was

put up against the school elite and came last; exhausted. My training in lifesaving

at Bloxwich baths never fitted me up for speed trials. In what remained of that

academic year neither the school nor I discovered what I was good at. The head

of house reported at the end of it that he was disappointed at my lack of contribution

to the achievements of the house; a sting that urged me to do better in the upper

sixth.

| Buckling

down in the Upper Sixth It was against this background

that I decided to bite the bullet for my final school year and live up to its

self-serving motto, "Not for self but for school".

In my final year

I did discover some useful things I could do and it was Cannock Grammar School

that provided for it. Scripture was introduced to the curriculum for the first

time taking the place of my long distance correspondence course with Miss Baker.

As a consequence of her endeavours I won the school competition for essay writing

in a discourse on 'Christianity versus Communism'. I am not sure if anyone else

entered the competition but I still have the book Miss Baker recommended I ask

for, 'Personalities of the Old Testament' by James which was presented in a grand

ceremony at Leeds Town Hall. I still value it as a memento of Cannock Grammar

School.

A Baptist minister, Mr Nettleship, was recruited to teach scripture

for the first time in West Leeds' history and guide me through my A level syllabus.

In his first lesson he was naïve enough to ask the upper sixth what hymns

they knew. The response was a spontaneous rendition of the rugby club version

of the exploits of the "Monks of St Bernard", a reaction which I could

not see being tolerated by Miss Baker at Cannock Grammar School. The introduction

of scripture into the school was not perhaps the most useful contribution I could

have made and I felt truly guilty that the Baptist minister had been dragged out

of his true vocation on my account.

Thinking of the Boys' interests in the

exploits of the Monks of St Bernard brought back memories of Mary Flynne, a devout

Catholic, asking Miss Baker what the 'Immaculate Conception' was, only to be told

that she would consider it for the next lesson. Eagerly awaited by some, the anticipated

exposition never materialised and no one saw fit to raise the question again.

I think Mary genuinely wanted to know the religious significance of the question,

but the boys of West Leeds would have had 'testing' motives for asking it. The

musical enthusiasm for hymn singing shown in Mr Nettleship's first lesson, was

in marked contrast to efforts to extract an audible hymn in the Head Teacher's

morning daily assembly.

My second opportunity came when the school arranged

its annual concert for invited guests. Contributions were invited from pupils

but the expected staff contribution never materialised. I suggested the formation

of a choir and, as there was no musical tradition in the school, I was left to

get on with it. Music was consigned to wooden huts at the far end of the cricket

pitch to avoid disturbing the school itself. What music there was 'in school'

was confined to the one hymn the head teacher seemed to know, "New every

morning is the love…" which was groaned at every morning assembly by

broken voices. Suggesting a choir to sing in front of invited guests was therefore

a high-risk strategy and I was no Gareth Malone.

I anticipated forming a balanced

four-part harmony octet of boys I knew from the renowned Bramley Parish Church

choir. I was surprised when 24 boys from various local church choirs turned up

when the word got round. It was then that Mr Bailey the music teacher from Cannock

Grammar School came to the rescue. He sent me 25 copies of music that we had been

singing in his choir; "Ave Verum", "O who will o'er the Downs so

free" and "All in the April Evening". The choir boys, all from

local churches were well accomplished and didn't require much coaching from me.

One of them was a good pianist and accompanied the choir which I was elected to

conduct. Permitted to practice in the school hall, our efforts were clearly heard

and in the end one hundred boys applied to join. It might have got out of hand

but, in an exercise of self-discipline the boys organised auditions and 'approved'

a further 25. Mr Bailey helped out again by furnishing a further 25 copies.

Hearing

the rehearsals it was assumed by the Head that the concert was well organised

by the staff and that their contribution was well in hand and it was only discovered

it wasn't a week before the event. He went round fretting about the invited guests.

It was rescued at a late stage by the boys themselves volunteering to read intellectual

passages and a few instrumental performances. The expected staff contribution

never materialised. The greatly relieved head teacher, not known for expressing

gratitude, did so on this occasion. I never did quite understand how it was that

the boys managed, or were allowed to manage, their own destiny. I think it was

something to do with the hierarchical traditions of the sixth and the fact that

they were referred to by the title 'Mr', a bit like a surgeon.

It was surprising

that the school was not aware of the raw talent that existed within its cloisters.

Such talent could have been harvested for school assembly to lead such choruses

as, "Thine be the Glory", but assemblies were seen as an obligatory

chore and "Umph" in assembly was not part of the school prospectus.

| Sports

Day Sports day was an entirely different matter.

It was the highlight of the year when pride was at stake and the elite sportsmen

from each house vigorously competed for the coveted house trophy. Hook house was

in the running that year but it was close. Not being an athlete, I was content

to encourage the team of supreme athletes from the side-lines where I had formed

a small orchestra, playing second fiddle, to add atmosphere to the occasion. My

unsolicited last minute contribution, for which I had not trained, was to run

in the 4 x 400 relay around the cricket pitch which was the final deciding event.

I was given a pair of ill-fitting spikes and told that I would take the final

leg, be given a substantial lead and in no way to drop the baton, or lose that

lead.

I was given a lead, the spikes gripped the turf and hurt like hell, reminding

me of my obligation with every stride, and sheer terror drove my legs like pistons

to the tape. Perhaps that miraculous strength was down to the power of prayer,

as a result of introducing scripture to the school, or perhaps the milk-round.

Hook house won that race and house trophy for that year. The scene was like something

out of "Harry Potter" and the emotion like something out of "To

Serve Them All Our Days". | Head

Boy for a day. Schooldays were put behind me (

or so I thought), uniform was discarded, no more responsibilities ( or so I thought)

and exam results were awaited; and then I received a letter from the headmaster.

He would like to promote me to Head Boy, for one day in order that I could make

the head-boy's speech at the Old Boys' society dinner. The real head-boy would

be in Cambridge so once again I was required to play second fiddle. Perhaps he

knew a thing or two about that dinner.

The dinner was a long standing traditional

black-tie affair. It was always held in the large banqueting hall of the Wellesley

Hotel in the centre of Leeds. I only had the pinstripe suit that I had acquired

after the romantic evening dance with Ann in my emerald green Cannock Grammar

School jacket. Much to the annoyance of Janet, the second girl I had allowed myself

to be fixed up with, I now sported a Frank Sinatra trilby to accompany my pinstriped

suit. So I now considered myself to be 'in fashion'. The hat saved me from a second

unsolicited romantic relationship after which and I finally made a lifelong decision

of my own.

Preparing a speech for the Old Boys' dinner was not difficult because

I had plenty of material in the comparison between the two grammar schools. It

was easy to butter up people from Yorkshire by appealing to their pride in their

triumphs, which I could see from the perspective of an 'outsider'. Unaware of

the audience, I had prepared a line that I thought might be received with a wry

smile or polite titter. It was to say that when I arrived at West Leeds from Cannock

Grammar School, I said the same as Charles 1st when he entered parliament……

The audience mostly comprised members of the old boy's rugby club who at that

stage, to put it politely were well oiled, erupted. I had not got the quotation

out before the place was in uproar with table thumping and foot stamping and Yorkshire

beer spilling over the starched white linen table cloths from raised glasses.

The Head Teacher, Mr Barnshaw woken from his contemplative slumbers, like Godfrey

out of Dad's Army, or Tommy Cooper caught in the headlights, was heard to ask,

"What was that? What was that? Yes, turning a 'Co. Ed.' Into 'single sex'

had been indeed a retrograde step and the boys were sensitive about losing their

'birds'.

| Epilogue. The

story of my transition from CGS to WLBS might have ended there but, twenty years

later, there was an opportunity to fulfil the obligation of the school motto "Non

Sibi Sed Ludo". The school, by that time, had become 'comprehensive' but

still retained much of the ethos of the old grammar school including the uniform

and motto. The image of the school represented elitism to the City Council who

wanted to transfer the boys to the girls' school, rename it, demolish the old

building and eradicate any vestige of its educational influence. The board of

governors, which I chaired, was split on the matter and the local councillors,

who had never been to a grammar school, hated the place. It was obvious to me

that premises were unsuitable for teaching in a modern environment, but the building

was a significant and notable landmark in the environment. With a little insider

knowledge, I secretly conspired with members of staff to get the building listed.

It was, much to the inconvenience of the City Council, but a 'worthy' compromise.

The

school was eventually transformed into maisonettes and is now known as the Old

School Lofts. They tower over the local community, proudly as a monument to past

educational glories. It is likely that, had a young lad from Cannock Grammar School,

not been unwillingly hauled north, the school building, which is half a mile away

from where I now live, and pass on a daily basis, might not be standing. The question

remains as to which of the school motto's is the more enduring; to 'live for your

school' or to 'live worthily'. West Leeds is the school I am constantly reminded

of; Cannock Grammar School is the school I shall never forget. |

|